La nutrición celular es un proceso complejo e indispensable para la conservación de la vida y el adecuado funcionamiento de cada uno de los tejidos del cuerpo (1). Este inicia con la absorción de los nutrientes en el tubo digestivo, su paso desde los tejidos adyacentes a la célula irrigados por los capilares sanguíneos, matriz extracelular y los procesos de incorporación y metabolismo (2). Las alteraciones en cada uno de los pasos implicados en el proceso de nutrición celular esta relacionado con múltiples enfermedades agudas y crónicas así como el deterioro de la calidad de vida (3,4). En este artículo se abordan aspectos referentes a la nutrición celular y su regulación y cómo la apiterapia contribuye a mejorar este proceso.

Proceso de nutrición celular

Son varios los pasos que ocurren dentro del proceso de nutrición celular. A continuación, se exploran los más relevantes:

Microbioma intestinal. El microbioma intestinal afecta de muchas formas el proceso de nutrición celular, de hecho, sus alteraciones están relacionadas con el desarrollo múltiples enfermedades metabólicas, degenerativas e inflamatorias (5–7). Las alteraciones de la flora bacteriana producen inflamación sistémica y anomalías en el funcionamiento del sistema inmunológico que producen a su vez modificaciones en el estado metabólico de las células (8,9). La flora bacteriana tambien modula la expresión genético en casi todos los tejidos, siendo relevante su efecto sobre el sistema nervioso, músculo, cartílago y hueso (10,11). Las anormalidades en el microbioma también han mostrado relación con la velocidad de absorción de nutrientes; especies de Bacteroidetes han mostrado modificar de forma significativa la disponibilidad para receptores de ácidos grasos y por vía incrementan su absorción y modifican las señales de saciedad facilitando la ganancia de peso (12). Los transportadores de carbohidratos también muestran modificaciones en su patrón de expresión cuando se altera el microbioma intestinal (13).

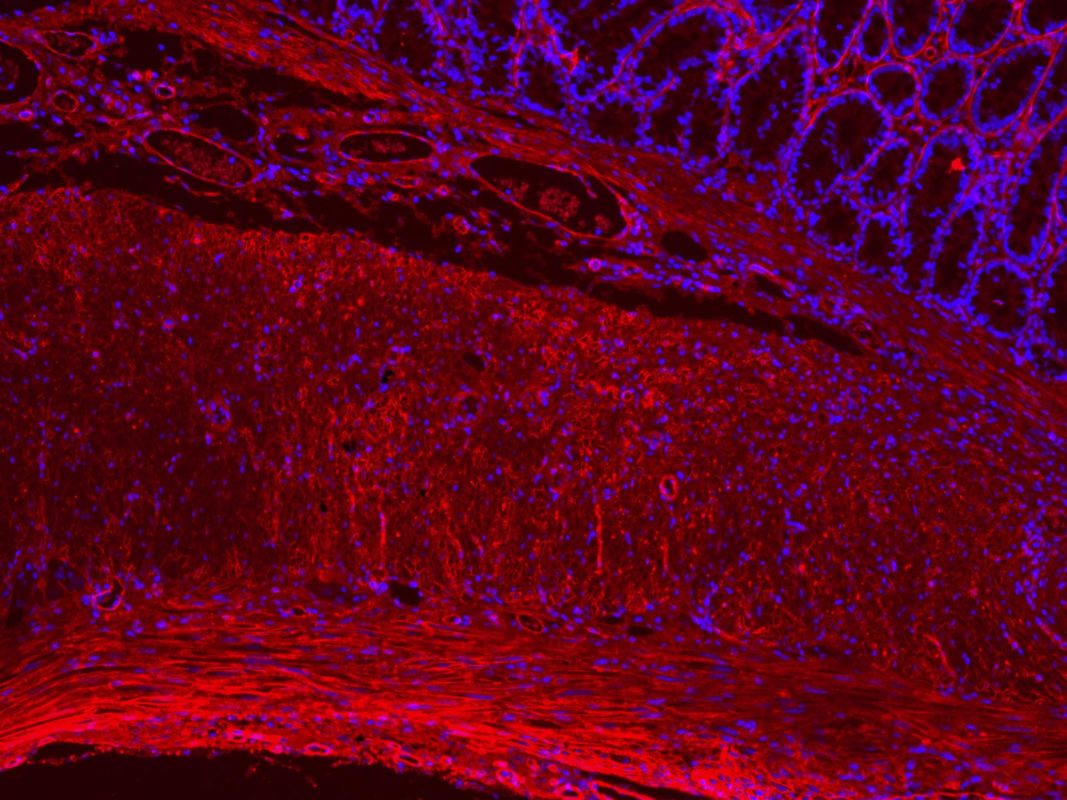

Microcirculación. El flujo sanguíneo adecuado es necesario e indispensable para lograr que los nutrientes y moléculas lleguen hasta las células. El proceso de envejecimiento y la acción de los radicales libres con el tiempo producen una alteración microvascular que dificulta la llegada de moléculas al microambiente celular, afecta su función e incrementa la velocidad con que se produce el envejecimiento (14,15). La función endotelial es por supuesto trascendental en el mantenimiento del flujo sanguíneo. La inflamación crónica, el envejecimiento celular y el estrés oxidativo son factores que afectan la función endotelial, alteran la regulación del flujo sanguíneo y conducen al daño permanente de las células endoteliales (16–18).

Inflamación crónica. La inflamación crónica produce modificaciones fenotípicas en diferentes poblaciones celulares (19–21). El consumo de algunos alimentos esta relacionado con la perpetuación de la inflamación, caso particular el del azúcar refinada que produce una sobreactivación de la via del mTOR (blanco mamífero de la rapamicina) (22). La inflamación crónica altera el microambiente celular y afecta la capacidad de la célula para captar nutrientes (23). La inflamación crónica es un paso facilitador del reemplazo del tejido funcional por fibra no funcional que por supuesto altera también la función celular (24,25).

Comunicación neuroinmunoendocrina. Mediante la función de la red de comunicación neuroinmunoendocrina se comunican a las células del cuerpo información necesaria para su sincronización y ritmo biológico de actividad (26,27). Las alteraciones en esta comunicación modifican el ritmo metabólico de las células y la velocidad de captación de nutrientes (28).

Estado metabólico de la célula. El nivel de actividad de la célula modula los nutrientes que requiere. La intensidad del proceso metabólico esta determinada en buena medida por señales externas siendo las hormonas una de las principales (29).

Función mitocondrial. La función de la mitocondria es esencial dentro del proceso metabólico de las células. Cuando el estrés oxidativo excede en su intensidad a las capacidades de los sistemas de control se activa por vía mitocondrial la vía de la muerte celular programada, este proceso esta implicado en muchas de las enfermedades degenerativas (30). La mitocondria modula la expresión genética y puede inducir modificaciones epigenéticas, la alteración en su función interrumpe la producción de energía a nivel celular y es uno de los enlaces que se han propuesto para entender los efectos negativos del estrés psicológico a largo plazo (31).

Activar la nutrición celular. Efectos de la apiterapia

La apiterapia ejerce diferentes acciones que estan implicados dentro del proceso de nutrición celular.

Efecto prebiótico y regulación de la disbiosis. La miel de abejas y el polen apícola regulan la flora bacteriana y contribuyen a su normalización mediante un efecto prebiótico (32,33).

Control del daño endotelial y microvascular. El veneno de abejas, propóleo, miel y jalea real contribuyen al control del daño endotelial mediante la regulación de los niveles de glucemia y colesterol, control de la inflamación local en el endotelio y efecto secuestrante de los radicales libres (34–37).

Control del proceso inflamatorio. Los productos de la colmena, principalmente el veneno de abejas y propóleo modulan la función del factor nuclear kappa beta implicado en la perpetuación de la respuesta inflamatoria en los tejidos (38–40).

Prevención de la fibrosis. El veneno de abejas reduce la formación de fibra no funcional en los tejidos crónicamente inflamados (41).

Regulación de la comunicación neuroinmunoendocrina. La jalea real y la miel de abejas contribuyen a la regulación de la función del sistema nervioso central mediante la modulación de la liberación de neurotransmisores y la liberación de hormonas (42,43). El veneno de abejas al modular la función de los linfocitos y macrófagos facilita la comunicación de estas células con otros tejidos (39,44).

Regulación del estado metabólico de la célula. La miel de abejas facilita la captación de glucosa en la célula e incrementa su sensibilidad a la insulina (45). El polen apícola aporta nutrientes como la vitamina B12, vitamina D, calcio y zinc necesarios para el funcionamiento celular (46).

Control del estrés oxidativo. La mayoría de productos de la colmena, principalmente la miel de abejas y el propóleo, poseen gran capacidad antioxidante que mitiga el daño oxidativo de las mitocondrias (47–49). La miel colombiana tiene la mayor capacidades antioxidantes descritas en la literatura.

Si te gustó este artículo te invitamos a compartirlo y suscribirte en el link «Newsletter» para recibir más información y contenidos relacionados

Referencias bibliográficas

1. Paul L. Diet, nutrition and telomere length. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2011.

2. Jessop NS. Aspects of cellular energetics. In: Farm animal metabolism and nutrition. 2009.

3. Amine EK, Baba NH, Belhadj M, Deurenberg-Yap M, Djazayery A, Forrestre T, et al. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organization – Technical Report Series. 2003.

4. Jang H, Serra C. Nutrition, Epigenetics, and Diseases. Clin Nutr Res. 2014;

5. Catinean A, Neag MA, Mitre AO, Bocsan CI, Buzoianu AD. Microbiota and Immune-Mediated Skin Diseases—An Overview. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2019 Aug 21;7(9):279. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2607/7/9/279

6. Chang C-S, Kao C-Y. Current understanding of the gut microbiota shaping mechanisms. J Biomed Sci [Internet]. 2019 Dec 21;26(1):59. Available from: https://jbiomedsci.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12929-019-0554-5

7. Sterlin D, Fadlallah J, Slack E, Gorochov G. The antibody/microbiota interface in health and disease. Mucosal Immunol [Internet]. 2019 Aug 14; Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41385-019-0192-y

8. Collins KH, Paul HA, Reimer RA, Seerattan RA, Hart DA, Herzog W. Relationship between inflammation, the gut microbiota, and metabolic osteoarthritis development: studies in a rat model. Osteoarthr Cartil [Internet]. 2015 Nov;23(11):1989–98. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1063458415008559

9. Boulangé CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J, Nicholson JK, Dumas M-E. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med [Internet]. 2016 Dec 20;8(1):42. Available from: http://genomemedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13073-016-0303-2

10. Stols-Gonçalves D, Tristão LS, Henneman P, Nieuwdorp M. Epigenetic Markers and Microbiota/Metabolite-Induced Epigenetic Modifications in the Pathogenesis of Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, Type 2 Diabetes, and Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr Diab Rep [Internet]. 2019 Jun 1;19(6):31. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11892-019-1151-4

11. Ticinesi A, Lauretani F, Milani C, Nouvenne A, Tana C, Del Rio D, et al. Aging Gut Microbiota at the Cross-Road between Nutrition, Physical Frailty, and Sarcopenia: Is There a Gut–Muscle Axis? Nutrients [Internet]. 2017 Nov 30;9(12):1303. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/9/12/1303

12. Samuel BS, Shaito A, Motoike T, Rey FE, Backhed F, Manchester JK, et al. Effects of the gut microbiota on host adiposity are modulated by the short-chain fatty-acid binding G protein-coupled receptor, Gpr41. Proc Natl Acad Sci [Internet]. 2008 Oct 28;105(43):16767–72. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.0808567105

13. Swartz TD, Duca FA, de Wouters T, Sakar Y, Covasa M. Up-regulation of intestinal type 1 taste receptor 3 and sodium glucose luminal transporter-1 expression and increased sucrose intake in mice lacking gut microbiota. Br J Nutr [Internet]. 2012 Mar 14;107(5):621–30. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0007114511003412/type/journal_article

14. Liu Y, Bloom SI, Donato AJ. The role of senescence, telomere dysfunction and shelterin in vascular aging. Microcirculation [Internet]. 2019;26(2):e12487. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29924435

15. Machin DR, Bloom SI, Campbell RA, Phuong TTT, Gates PE, Lesniewski LA, et al. Advanced age results in a diminished endothelial glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Circ Physiol [Internet]. 2018 Sep 1;315(3):H531–9. Available from: https://www.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/ajpheart.00104.2018

16. Förstermann U, Xia N, Li H. Roles of Vascular Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res [Internet]. 2017 Feb 17;120(4):713–35. Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309326

17. López-Domènech S, Bañuls C, Díaz-Morales N, Escribano-López I, Morillas C, Veses S, et al. Obesity impairs leukocyte-endothelium cell interactions and oxidative stress in humans. Eur J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2018 Aug;48(8):e12985. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/eci.12985

18. He L, Zhou B. The Development and Regeneration of Coronary Arteries. Curr Cardiol Rep [Internet]. 2018 Jul 25;20(7):54. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11886-018-0999-2

19. Maurizi G, Della Guardia L, Maurizi A, Poloni A. Adipocytes properties and crosstalk with immune system in obesity-related inflammation. J Cell Physiol [Internet]. 2018 Jan;233(1):88–97. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/jcp.25855

20. Zhang C, Yu P, Ma J, Zhu L, Xu A, Zhang J. Damage and Phenotype Change in PC12 Cells Induced by Lipopolysaccharide Can Be Inhibited by Antioxidants Through Reduced Cytoskeleton Protein Synthesis. Inflammation [Internet]. 2019 Sep 6; Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10753-019-01089-9

21. Bystrom J, Clanchy FIL, Taher TE, Al-Bogami M, Ong VH, Abraham DJ, et al. Functional and phenotypic heterogeneity of Th17 cells in health and disease. Eur J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2019 Jan;49(1):e13032. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/eci.13032

22. Moling O, Gandini L. Sugar and the Mosaic of Autoimmunity. Am J Case Rep [Internet]. 2019 Sep 15;20:1364–8. Available from: https://www.amjcaserep.com/abstract/index/idArt/915703

23. Wang T, Nasser MI, Shen J, Qu S, He Q, Zhao M. Functions of Exosomes in the Triangular Relationship between the Tumor, Inflammation, and Immunity in the Tumor Microenvironment. J Immunol Res [Internet]. 2019 Aug 1;2019:1–10. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jir/2019/4197829/

24. Mack M. Inflammation and fibrosis. Matrix Biol [Internet]. 2018 Aug;68–69:106–21. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0945053X1730375X

25. Meng X-M. Inflammatory Mediators and Renal Fibrosis. In 2019. p. 381–406. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-13-8871-2_18

26. Morris CJ, Aeschbach D, Scheer FAJL. Circadian system, sleep and endocrinology. Mol Cell Endocrinol [Internet]. 2012 Feb;349(1):91–104. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0303720711005375

27. Yan L, Silver R. Neuroendocrine underpinnings of sex differences in circadian timing systems. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol [Internet]. 2016 Jun;160:118–26. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960076015301114

28. Tena-Sempere M. Neuroendocrine control of metabolism and reproduction. Nat Rev Endocrinol [Internet]. 2017 Feb 6;13(2):67–8. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/nrendo.2016.216

29. Panda S. Circadian physiology of metabolism. Science (80- ) [Internet]. 2016 Nov 25;354(6315):1008–15. Available from: http://www.sciencemag.org/lookup/doi/10.1126/science.aah4967

30. Sinha K, Das J, Pal PB, Sil PC. Oxidative stress: the mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways of apoptosis. Arch Toxicol [Internet]. 2013 Jul 30;87(7):1157–80. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00204-013-1034-4

31. Picard M, McEwen BS. Psychological Stress and Mitochondria. Psychosom Med [Internet]. 2018;80(2):126–40. Available from: http://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00006842-201802000-00002

32. Miguel M, Antunes M, Faleiro M. Honey as a Complementary Medicine. Integr Med Insights [Internet]. 2017 Jan 24;12:117863371770286. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1178633717702869

33. Denisow B, Denisow-Pietrzyk M. Biological and therapeutic properties of bee pollen: a review. J Sci Food Agric [Internet]. 2016 Oct;96(13):4303–9. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/jsfa.7729

34. Shkenderov S, Koburova K. Adolapin–a newly isolated analgetic and anti-inflammatory polypeptide from bee venom. Toxicon [Internet]. 1982;20(1):317–21. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7080045

35. Bueno-Silva B, Franchin M, Alves C de F, Denny C, Colón DF, Cunha TM, et al. Main pathways of action of Brazilian red propolis on the modulation of neutrophils migration in the inflammatory process. Phytomedicine [Internet]. 2016 Dec 1;23(13):1583–90. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27823622

36. Alagwu EA, Okwara JE, Nneli RO, Osim EE. Effect of honey intake on serum cholesterol, triglycerides and lipoprotein levels in albino rats and potential benefits on risks of coronary heart disease. Niger J Physiol Sci [Internet]. 2011 Dec 20;26(2):161–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22547185

37. Watadani R, Kotoh J, Sasaki D, Someya A, Matsumoto K, Maeda A. 10-Hydroxy-2-decenoic acid, a natural product, improves hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in obese/diabetic KK-Ay mice, but does not prevent obesity. J Vet Med Sci [Internet]. 2017 Sep 29;79(9):1596–602. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28740028

38. Tornatore L, Thotakura AK, Bennett J, Moretti M, Franzoso G. The nuclear factor kappa B signaling pathway: integrating metabolism with inflammation. Trends Cell Biol [Internet]. 2012 Nov;22(11):557–66. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0962892412001407

39. Lee JH, Kwon YB, Han HJ, Mar WC, Lee HJ, Yang IS, et al. Bee venom pretreatment has both an antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effect on carrageenan-induced inflammation. J Vet Med Sci [Internet]. 2001 Mar;63(3):251–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11307924

40. Conti BJ, Santiago KB, Cardoso EO, Freire PP, Carvalho RF, Golim MA, et al. Propolis modulates miRNAs involved in TLR-4 pathway, NF-κB activation, cytokine production and in the bactericidal activity of human dendritic cells. J Pharm Pharmacol [Internet]. 2016 Dec;68(12):1604–12. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jphp.12628

41. Lee W-R, Pak S, Park K-K. The Protective Effect of Bee Venom on Fibrosis Causing Inflammatory Diseases. Toxins (Basel) [Internet]. 2015 Nov 16;7(12):4758–72. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6651/7/11/4758

42. Ghanbari E, Khazaei MR, Khazaei M, Nejati V. Royal Jelly Promotes Ovarian Follicles Growth and Increases Steroid Hormones in Immature Rats. Int J Fertil Steril [Internet]. 2018 Jan;11(4):263–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29043701

43. Viuda-Martos M, Ruiz-Navajas Y, Fernández-López J, Pérez-Álvarez JA. Functional Properties of Honey, Propolis, and Royal Jelly. J Food Sci [Internet]. 2008 Nov;73(9):R117–24. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00966.x

44. Han SM, Park KK, Nicholls YM, Macfarlane N, Duncan G. Effects of honeybee (Apis mellifera) venom on keratinocyte migration in vitro. Pharmacogn Mag [Internet]. 2013 Jul;9(35):220–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23930005

45. Lori G, Cecchi L, Mulinacci N, Melani F, Caselli A, Cirri P, et al. Honey extracts inhibit PTP1B, upregulate insulin receptor expression, and enhance glucose uptake in human HepG2 cells. Biomed Pharmacother [Internet]. 2019 May;113:108752. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0753332218346948

46. Bogdanov S. Pollen : Production , Nutrition and Health : A Review. Bee Prod Sci [Internet]. 2014;(February):1–35. Available from: www.bee-hexagon.net

47. Sahin H. Honey as an apitherapic product: its inhibitory effect on urease and xanthine oxidase. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem [Internet]. 2015 May 5;1–5. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/14756366.2015.1039532

48. Daugsch A, Moraes CS, Fort P, Park YK. Brazilian red propolis – Chemical composition and botanical origin. Evidence-based Complement Altern Med. 2008;5(4):435–41.

49. Pasupuleti VR, Sammugam L, Ramesh N, Gan SH. Honey, Propolis, and Royal Jelly: A Comprehensive Review of Their Biological Actions and Health Benefits. Oxid Med Cell Longev [Internet]. 2017;2017:1259510. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28814983