La nutrición es un proceso complejo e indispensable para la conservación de la vida y el adecuado funcionamiento de cada uno de los tejidos del cuerpo (1). Este inicia con la absorción de los nutrientes en el tubo digestivo, su paso desde los tejidos adyacentes a la célula irrigados por los capilares sanguíneos, matriz extracelular y los procesos de incorporación y metabolismo (2). Las alteraciones en cada uno de los pasos implicados en el proceso de nutrición está relacionado con múltiples enfermedades agudas y crónicas así como el deterioro de la calidad de vida (3,4).

Los avances en el estudio del microbioma, genómica, proteómica, transcriptómica y epigenómica han modificado la forma en la cual se entiende el efecto de los alimentos y han dado lugar al entendimiento de las funciones que poseen algunos de ellos: se trata de los alimentos funcionales, es decir, aquellos que son útiles en la prevención y manejo de enfermedades (5). Los productos de la colmena (pan de abejas, miel, jalea real, propóleo y polen) son alimentos con importantes propiedades en términos de la prevención y tratamiento de diferentes enfermedades.

Jalea real

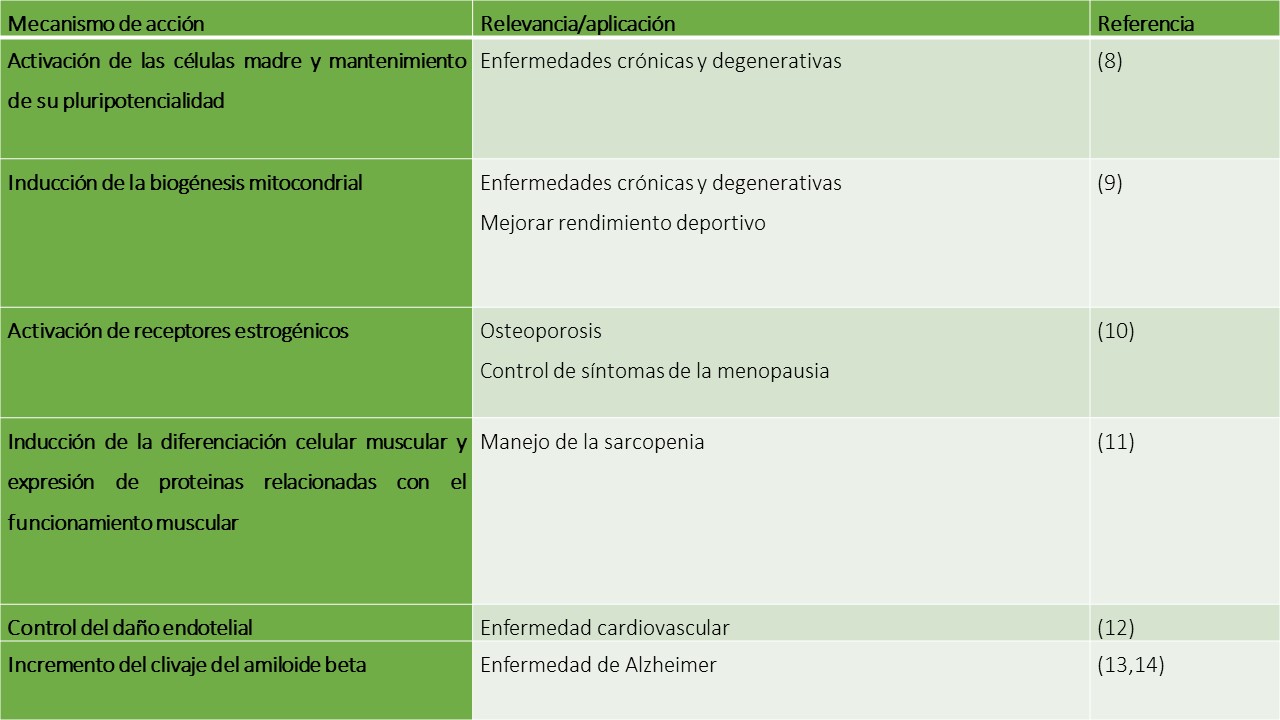

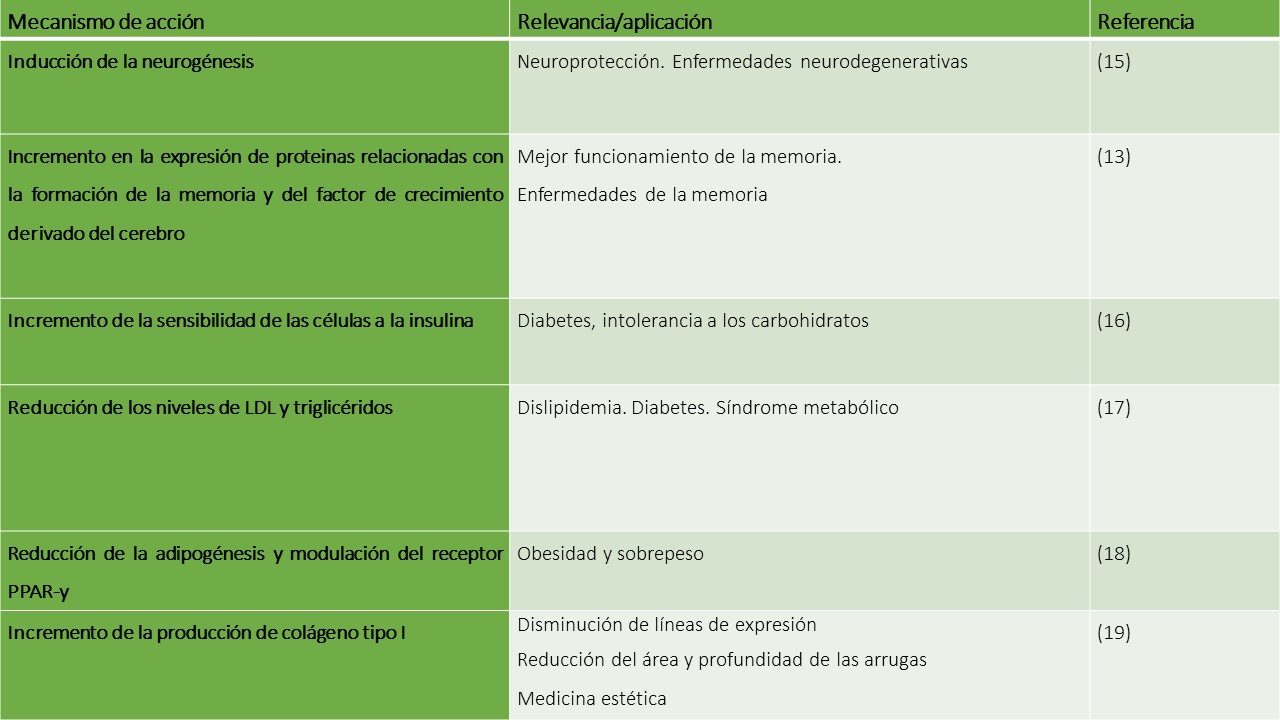

La jalea real es una sustancia que secretan las abejas desde las glándulas ubicadas en la región hipofaringea. Las abejas utilizan la jalea real como alimento para las larvas y la abeja reina. Es una sustancia de color amarillo, viscosa y de sabor amargo (6). La jalea real está compuesta por agua, ácidos grasos y proteínas (7). Dentro de ellos la proteína mayor de la jalea real y el 17β-estradiol, 17α-etinilestradiol, ácido 10-hidroxidecanoico y el ácido 10-hidroxitrans-2 decanoico son de interés terapéutico reconocido.

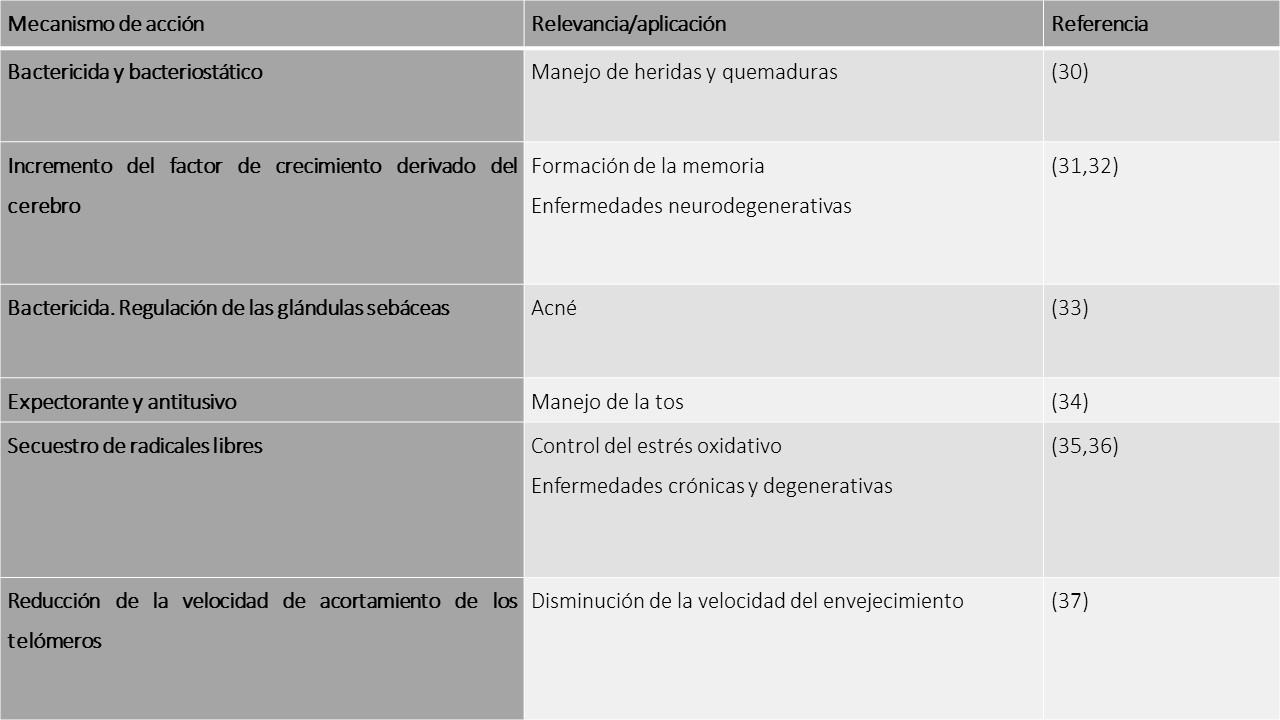

Los siguientes son mecanismos y aplicaciones de la jalea real:

Su administración puede ser por vía oral (500 a 1000 mg cada día) o tópica sobre las lesiones como ocurre en el caso de los beneficios sobre la piel.

Miel de abejas

La miel de abejas es un líquido viscoso generalmente de sabor dulce derivado del néctar de las flores o de las secreciones dulces de algunos tallos de las plantas. Las abejas introducen el néctar en su interior y lo transforman mezclándolo con enzimas como la invertasa que modifica su composición. En buena medida este proceso busca también reducir la humedad del líquido (25). Este proceso se da mediante la trofalaxis un mecanismo de transferencia de néctar de boca a boca y en el cual también participan los zánganos (26).

La composición de la miel es compleja aunque en su mayoría se encuentran carbohidratos (fructosa y glucosa principalmente) y agua. También es posible identificar aminoácidos, péptidos, vitaminas, minerales y agentes polifenólicos (27). En buena medida la utilidad de la miel de abejas debe sus propiedades terapéuticas a estos componentes polifenólicos. Estas composiciones varían de acuerdo a la región geográfica donde se ubica la colmena y a la fuente de alimento de las colmenas (28). De acuerdo a la fuente de alimento la miel puede ser clasificada como monofloral (al menos el 60% del néctar deriva de una única especie floral), multifloral (múltiples especies florales) o miel de mielada (el néctar deriva de secreciones dulces que dejan otros insectos y que han extraído de los tallos de los árboles), un tipo particular es el mielato que procede de los pinos (29) (28).

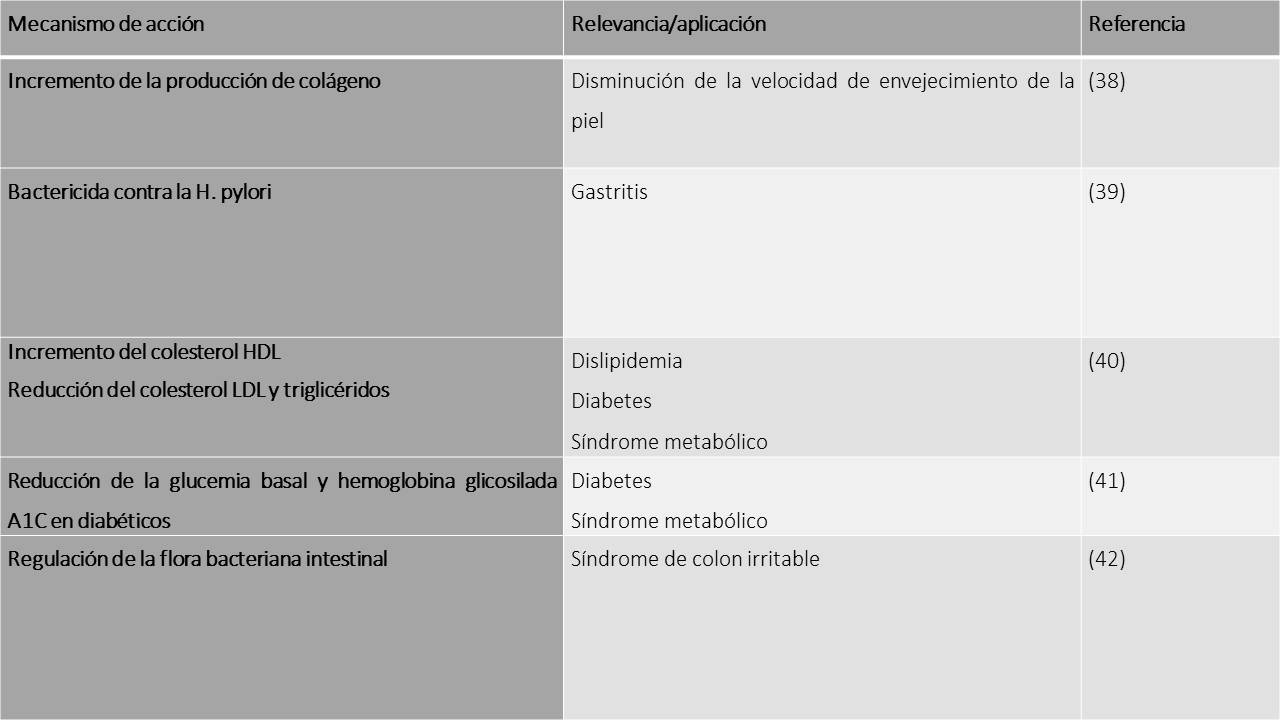

Los siguientes son mecanismos y aplicaciones de la miel de abejas:

La miel de abejas debe consumirse a razón de 15 a 50 gramos por día o tópica sobre las heridas.

Propóleo

Los propóleos son una mezcla de resinas que obtienen las abejas de las diferentes fuentes vegetales que se encuentran alrededor de la colmena los cuales son sometidos a algunas transformaciones enzimáticas por las abejas. A temperaturas bajas los propóleos son de consistencia dura y es utilizado por las abejas para sellar huecos en la colmena y protegerla de la invasión de microorganismos y parásitos, también se ha descrito que sirve para el reforzamiento estructural de la colmena y mitigar el efecto de las vibraciones sobre ella (43).

La composición es variable de acuerdo a la región geográfica y la vegetación de la zona de donde se obtenga sin embargo se identifican resinas, bálsamos, aceites volátiles y otras sustancias orgánicas donde es posible identificar compuestos polifenólicos y flavonoides (44).

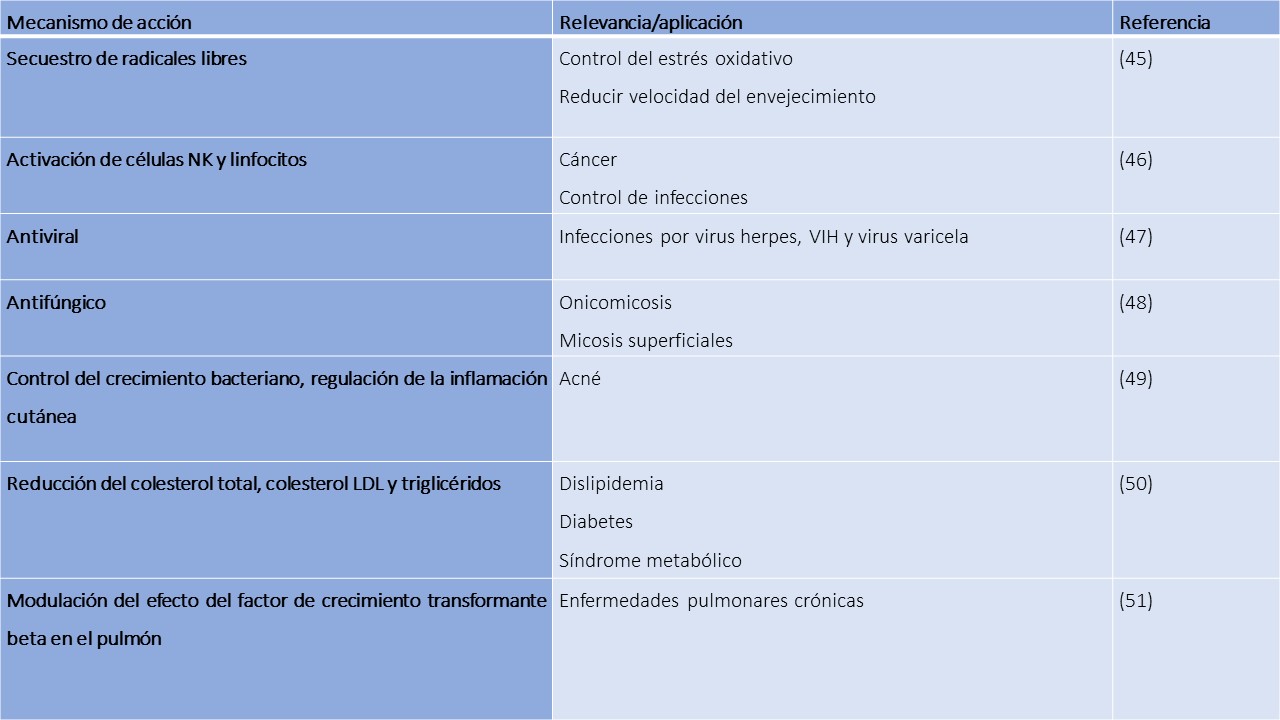

Los siguientes son mecanismos y aplicaciones del propóleo:

Debe indicarse a razón de 5 a 10 ml tomados cada día o 2 a 4 aplicaciones en el sitio afectado en el caso del manejo de heridas e infecciones de uñas o piel.

Polen de abejas

Las abejas se cuentan dentro del grupo de animales capaces de consumir el polen. En sus patas poseen adaptaciones en forma de cestas para cargar los granos hasta la colmena. El tiempo de mayor consumo de polen es durante su fase de larva ya que en momentos posteriores de su ciclo vital se utiliza más el néctar como fuente de alimento (52). Las toman los granos de polen de las plantas y lo llevan a la colmena en donde se realizan transformaciones mediadas por algunas enzimas como la amilasa y la catalasa para poder utilizarlo como alimento (53).

Al menos 200 componentes distintos han sido identificados en el polen. Dentro de los componentes del polen se encuentran proteínas y aminoácidos (hasta 50% de su composición), carbohidratos (hasta un 30%), lípidos (hasta un 7%), fibra (hasta un 20% de la composición) y otros compuestos como ácidos nucleicos, vitaminas y minerales (54).

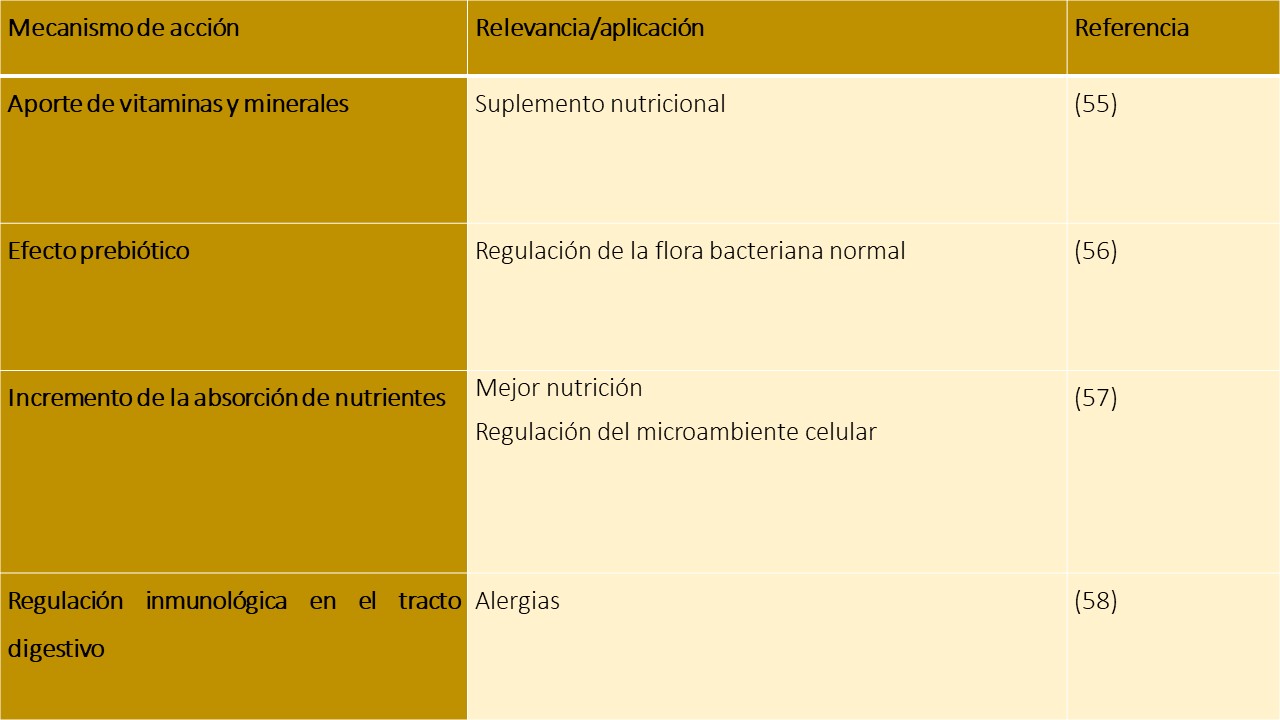

Los siguientes son mecanismos y aplicaciones del polen de abejas:

Cuando se consume en extracto etanólico se requiere el consumo de 5 a 10 ml cada día y 15 gramos diarios en presentación de gránulos.

Pan de abejas

Se trata de una mezcla de miel, cera y polen que sufre un proceso de fermentación láctica dentro de la colmena. Es un producto con un alto contenido de proteínas y aminoácidos, carbohidratos y ácidos grasos insaturados (59).

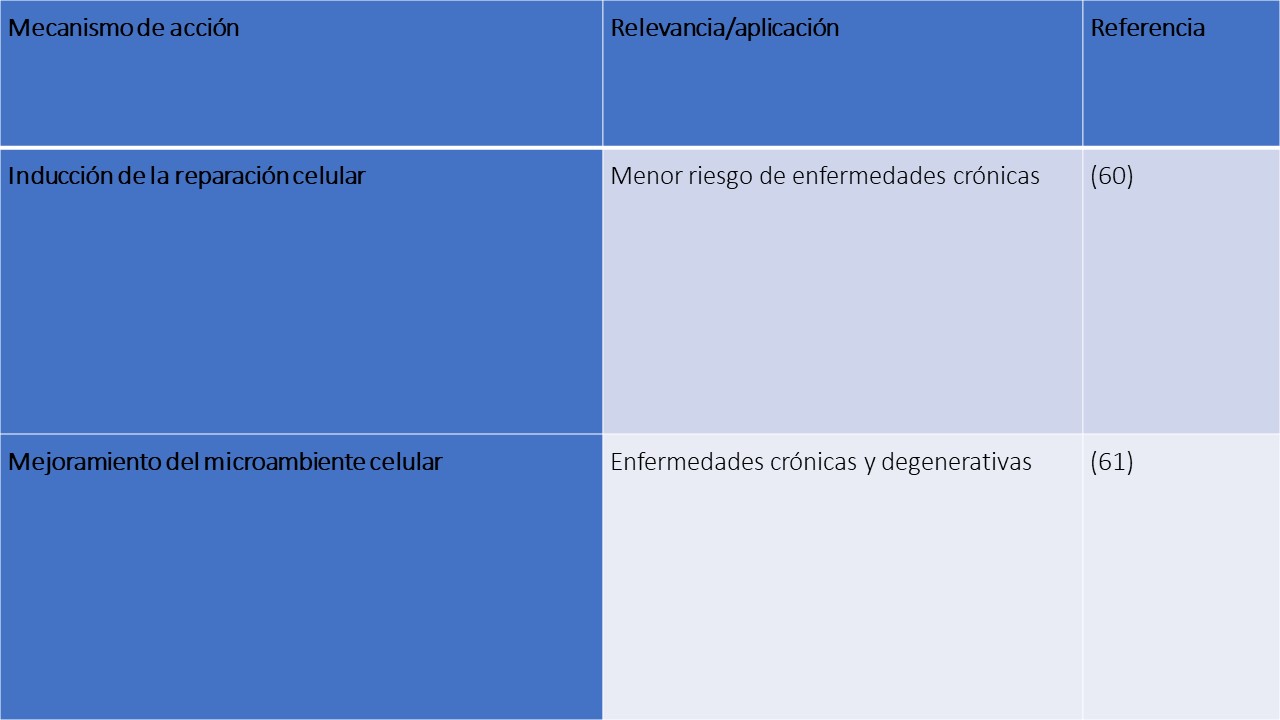

Los siguientes son mecanismos y aplicaciones del pan de abejas:

Este producto se indica a razón de 5 a 10 ml cada día.

Referencias bibliográficas

1. Paul L. Diet, nutrition and telomere length. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2011.

2. Jessop NS. Aspects of cellular energetics. In: Farm animal metabolism and nutrition. 2009.

3. Amine EK, Baba NH, Belhadj M, Deurenberg-Yap M, Djazayery A, Forrestre T, et al. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organization – Technical Report Series. 2003.

4. Jang H, Serra C. Nutrition, Epigenetics, and Diseases. Clin Nutr Res. 2014;

5. Calvo S, Gómez C, López C, Royo MÁ. Nutrición, salud y alimentos funcionales. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;

6. Melliou E, Chinou I. Chemistry and bioactivity of royal jelly from Greece. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53(23):8987–92.

7. Bogdanov S. Royal jelly, bee brood: composition, health, medicine: a review. Lipids [Internet]. 2011;(February):1–32. Available from: http://www.apitherapie.ch/files/files/Gelee/RJBookReview.pdf

8. Wan DC, Morgan SL, Spencley AL, Mariano N, Chang EY, Shankar G, et al. Honey bee Royalactin unlocks conserved pluripotency pathway in mammals. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2018 Dec 4;9(1):5078. Available from: http://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-06256-4

9. Takahashi Y, Hijikata K, Seike K, Nakano S, Banjo M, Sato Y, et al. Effects of Royal Jelly Administration on Endurance Training-Induced Mitochondrial Adaptations in Skeletal Muscle. Nutrients [Internet]. 2018 Nov 12;10(11):1735. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/10/11/1735

10. Sharif SN, Darsareh F. Effect of royal jelly on menopausal symptoms: A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract [Internet]. 2019 Nov;37:47–50. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1744388119301720

11. Niu K, Guo H, Guo Y, Ebihara S, Asada M, Ohrui T, et al. Royal Jelly Prevents the Progression of Sarcopenia in Aged Mice In Vivo and In Vitro. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci [Internet]. 2013 Dec 1;68(12):1482–92. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/biomedgerontology/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/gerona/glt041

12. Watadani R, Kotoh J, Sasaki D, Someya A, Matsumoto K, Maeda A. 10-Hydroxy-2-decenoic acid, a natural product, improves hyperglycemia and insulin resistance in obese/diabetic KK-Ay mice, but does not prevent obesity. J Vet Med Sci [Internet]. 2017 Sep 29;79(9):1596–602. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28740028

13. You M, Pan Y, Liu Y, Chen Y, Wu Y, Si J, et al. Royal Jelly Alleviates Cognitive Deficits and β-Amyloid Accumulation in APP/PS1 Mouse Model Via Activation of the cAMP/PKA/CREB/BDNF Pathway and Inhibition of Neuronal Apoptosis. Front Aging Neurosci [Internet]. 2019 Jan 4;10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00428/full

14. Pan Y, Xu J, Chen C, Chen F, Jin P, Zhu K, et al. Royal Jelly Reduces Cholesterol Levels, Ameliorates Aβ Pathology and Enhances Neuronal Metabolic Activities in a Rabbit Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Aging Neurosci [Internet]. 2018 Mar 5;10. Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00050/full

15. Hattori N, Nomoto H, Fukumitsu H, Mishima S, Furukawa S. Royal jelly and its unique fatty acid, 10-hydroxy-trans-2-decenoic acid, promote neurogenesis by neural stem/progenitor cells in vitro. Biomed Res [Internet]. 2007 Oct;28(5):261–6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18000339

16. Pourmoradian S, Mahdavi R, Mobasseri M, Faramarzi E, Mobasseri M. Effects of royal jelly supplementation on glycemic control and oxidative stress factors in type 2 diabetic female: A randomized clinical trial. Chin J Integr Med [Internet]. 2014 May 7;20(5):347–52. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11655-014-1804-8

17. Metwally Ibrahim SEL, Kosba AA. Royal jelly supplementation reduces skeletal muscle lipotoxicity and insulin resistance in aged obese rats. Pathophysiology [Internet]. 2018 Dec;25(4):307–15. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0928468018300117

18. Pandeya PR, Lamichhane R, Lee K-H, Kim S-G, Lee D-H, Lee H-K, et al. Bioassay-guided isolation of active anti-adipogenic compound from royal jelly and the study of possible mechanisms. BMC Complement Altern Med [Internet]. 2019 Dec 29;19(1):33. Available from: https://bmccomplementalternmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-018-2423-2

19. Park HM, Hwang E, Lee KG, Han S-M, Cho Y, Kim SY. Royal Jelly Protects Against Ultraviolet B–Induced Photoaging in Human Skin Fibroblasts via Enhancing Collagen Production. J Med Food [Internet]. 2011 Sep;14(9):899–906. Available from: http://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/jmf.2010.1363

20. Peng C-C, Sun H-T, Lin I-P, Kuo P-C, Li J-C. The functional property of royal jelly 10-hydroxy-2-decenoic acid as a melanogenesis inhibitor. BMC Complement Altern Med [Internet]. 2017 Dec 9;17(1):392. Available from: http://bmccomplementalternmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-017-1888-8

21. KOHNO K, OKAMOTO I, SANO O, ARAI N, IWAKI K, IKEDA M, et al. Royal Jelly Inhibits the Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines by Activated Macrophages. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem [Internet]. 2004 Jan 22;68(1):138–45. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1271/bbb.68.138

22. Sugiyama T, Takahashi K, Tokoro S, Gotou T, Neri P, Mori H. Inhibitory effect of 10-hydroxy-trans-2-decenoic acid on LPS-induced IL-6 production via reducing IκB-ζ expression. Innate Immun [Internet]. 2012 Jun;18(3):429–37. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21948282

23. Takahashi K, Sugiyama T, Tokoro S, Neri P, Mori H. Inhibition of interferon-γ-induced nitric oxide production by 10-hydroxy-trans-2-decenoic acid through inhibition of interferon regulatory factor-8 induction. Cell Immunol [Internet]. 2012;273(1):73–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S000887491100298X

24. Zahran AM, Elsayh KI, Saad K, Eloseily EMA, Osman NS, Alblihed MA, et al. Effects of royal jelly supplementation on regulatory T cells in children with SLE. Food Nutr Res [Internet]. 2016 Jan 24;60(1):32963. Available from: http://foodandnutritionresearch.net/index.php/fnr/article/view/960

25. Jr JW. Definition of Honey and Honey Products. Jour Assoc Off Anal Chem Jour Apicul Res. 1980;63(174):11–8.

26. White JW. Honey. Adv Food Res [Internet]. 1978;24:287–374. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/367113

27. Ball DW. The Chemical Composition of Honey. J Chem Educ [Internet]. 2007;84(10):1643. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ed084p1643

28. Da Silva PM, Gauche C, Gonzaga LV, Costa ACO, Fett R. Honey: Chemical composition, stability and authenticity. Vol. 196, Food Chemistry. 2016. p. 309–23.

29. Codex Alimentarius Commission. Standard For Honey [Internet]. Vol. 12, Codex Stan. 2001. p. 1–8. Available from: http://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FStandards%252FCODEX%2BSTAN%2B12-1981%252Fcxs_012e.pdf

30. Jull AB, Cullum N, Dumville JC, Westby MJ, Deshpande S, Walker N. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2015 Mar 6; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD005083.pub4

31. Azman KF, Zakaria R, Abdul Aziz CB, Othman Z. Tualang Honey Attenuates Noise Stress-Induced Memory Deficits in Aged Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev [Internet]. 2016;2016:1–11. Available from: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/omcl/2016/1549158/

32. Mustafa MZ, Zulkifli FN, Fernandez I, Mariatulqabtiah AR, Sangu M, Nor Azfa J, et al. Stingless Bee Honey Improves Spatial Memory in Mice, Probably Associated with Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Inositol 1,4,5-Triphosphate Receptor Type 1 ( Itpr1 ) Genes. Evidence-Based Complement Altern Med [Internet]. 2019 Dec 2;2019:1–11. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecam/2019/8258307/

33. Eady EA, Layton AM, Cove JH. A Honey Trap for the Treatment of Acne: Manipulating the Follicular Microenvironment to Control Propionibacterium acnes. Biomed Res Int [Internet]. 2013;2013:1–8. Available from: http://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2013/679680/

34. Oduwole O, Udoh EE, Oyo-Ita A, Meremikwu MM. Honey for acute cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018 Apr 10; Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD007094.pub5

35. Neamatallah T, El-Shitany NA, Abbas AT, Ali SS, Eid BG. Honey protects against cisplatin-induced hepatic and renal toxicity through inhibition of NF-κB-mediated COX-2 expression and the oxidative stress dependent BAX/Bcl-2/caspase-3 apoptotic pathway. Food Funct [Internet]. 2018;9(7):3743–54. Available from: http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C8FO00653A

36. Mohd Sairazi NS, K.N.S. S, Asari MA, Mummedy S, Muzaimi M, Sulaiman SA. Effect of tualang honey against KA-induced oxidative stress and neurodegeneration in the cortex of rats. BMC Complement Altern Med [Internet]. 2017 Dec 9;17(1):31. Available from: http://bmccomplementalternmed.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-016-1534-x

37. Nasir NFM, Kannan TP, Sulaiman SA, Shamsuddin S, Azlina A, Stangaciu S. The relationship between telomere length and beekeeping among Malaysians. Age (Omaha). 2015;37(3).

38. Majtan J, Kumar P, Majtan T, Walls AF, Klaudiny J. Effect of honey and its major royal jelly protein 1 on cytokine and MMP-9 mRNA transcripts in human keratinocytes. Exp Dermatol [Internet]. 2009 Oct 21;19(8):e73–9. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00994.x

39. Osato MS, Reddy SG, Graham DY. Osmotic effect of honey on growth and viability of Helicobacter pylori. Dig Dis Sci [Internet]. 1999 Mar;44(3):462–4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10080135

40. Bahrami M, Ataie-Jafari A, Hosseini S, Foruzanfar MH, Rahmani M, Pajouhi M. Effects of natural honey consumption in diabetic patients: an 8-week randomized clinical trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr [Internet]. 2009 Oct 10;60(7):618–26. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/09637480801990389

41. Nazir L, Samad F, Haroon W, Kidwai SS, Siddiqi S, Zehravi M. Comparison of glycaemic response to honey and glucose in type 2 diabetes. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64(1):69–71.

42. Miguel M, Antunes M, Faleiro M. Honey as a Complementary Medicine. Integr Med Insights [Internet]. 2017 Jan 24;12:117863371770286. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1178633717702869

43. König B. Plant sources of propolis. Bee World. 1985;66(4):136–9.

44. Bankova VS, CASTRO SL DE, C. M. Propolis: recent advances in chemistry and plant origin. Apidologie [Internet]. 2000;31:3–15. Available from: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00891696/document

45. Karapetsas A, Voulgaridou G-P, Konialis M, Tsochantaridis I, Kynigopoulos S, Lambropoulou M, et al. Propolis Extracts Inhibit UV-Induced Photodamage in Human Experimental In Vitro Skin Models. Antioxidants [Internet]. 2019 May 9;8(5):125. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/8/5/125

46. Sforcin JM. Biological Properties and Therapeutic Applications of Propolis. Phyther Res [Internet]. 2016 Jun;30(6):894–905. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ptr.5605

47. Münstedt K. Bee products and the treatment of blister-like lesions around the mouth, skin and genitalia caused by herpes viruses—A systematic review. Complement Ther Med [Internet]. 2019 Apr;43:81–4. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0965229919300275

48. Veiga FF, Costa MI, Cótica ÉSK, Svidzinski TIE, Negri M. Propolis for the Treatment of Onychomycosis. Indian J Dermatol [Internet]. 63(6):515–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30504984

49. Mazzarello V, Donadu M, Ferrari M, Piga G, Usai D, Zanetti S, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination of propolis, tea tree oil, and Aloe vera compared to erythromycin cream: two double-blind investigations. Clin Pharmacol Adv Appl [Internet]. 2018 Dec;Volume 10:175–81. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/treatment-of-acne-with-a-combination-of-propolis-tea-tree-oil-and-aloe-peer-reviewed-article-CPAA

50. Oršolić N, Landeka Jurčević I, Đikić D, Rogić D, Odeh D, Balta V, et al. Effect of Propolis on Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia and Atherogenic Indices in Mice. Antioxidants [Internet]. 2019 Jun 3;8(6):156. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/8/6/156

51. Kao H-F, Chang-Chien P-W, Chang W-T, Yeh T-M, Wang J-Y. Propolis inhibits TGF-β1-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition in human alveolar epithelial cells via PPARγ activation. Int Immunopharmacol [Internet]. 2013 Mar;15(3):565–74. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1567576912003967

52. Wappler T, Labandeira CC, Engel MS, Zetter R, Grímsson F. Specialized and Generalized Pollen-Collection Strategies in an Ancient Bee Lineage. Curr Biol [Internet]. 2015 Dec;25(23):3092–8. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960982215011008

53. Campos MGR, Bogdanov S, de Almeida-Muradian LB, Szczesna T, Mancebo Y, Frigerio C, et al. Pollen composition and standardisation of analytical methods. J Apic Res [Internet]. 2008 Jun 1;47(2):154–61. Available from: http://www.ibra.org.uk/articles/Pollen-composition-and-standardisation-of-analytical-methods

54. Ares AM, Valverde S, Bernal JL, Nozal MJ, Bernal J. Extraction and determination of bioactive compounds from bee pollen. J Pharm Biomed Anal [Internet]. 2017 Aug; Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0731708517314528

55. Bogdanov S. Pollen : Production , Nutrition and Health : A Review. Bee Prod Sci [Internet]. 2014;(February):1–35. Available from: www.bee-hexagon.net

56. Denisow B, Denisow-Pietrzyk M. Biological and therapeutic properties of bee pollen: a review. J Sci Food Agric [Internet]. 2016 Oct;96(13):4303–9. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/jsfa.7729

57. Ricigliano VA, Fitz W, Copeland DC, Mott BM, Maes P, Floyd AS, et al. The impact of pollen consumption on honey bee ( Apis mellifera ) digestive physiology and carbohydrate metabolism. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol [Internet]. 2017 Oct;96(2):e21406. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/arch.21406

58. Jannesar M, Sharif Shoushtari M, Majd A, Pourpak Z. Bee Pollen Flavonoids as a Therapeutic Agent in Allergic and Immunological Disorders. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol [Internet]. 2017 Jun;16(3):171–82. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28732430

59. Kaplan M, Karaoglu Ö, Eroglu N, Silici S. Fatty Acids and Proximate Composition of Beebread. Food Technol Biotechnol [Internet]. 2016;54(4). Available from: http://www.ftb.com.hr/images/pdfarticles/2016/October-December/ftb-54-497.pdf

60. Mărgăoan, Stranț, Varadi, Topal, Yücel, Cornea-Cipcigan, et al. Bee Collected Pollen and Bee Bread: Bioactive Constituents and Health Benefits. Antioxidants [Internet]. 2019 Nov 20;8(12):568. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/8/12/568

61. Sobral F, Calhelha R, Barros L, Dueñas M, Tomás A, Santos-Buelga C, et al. Flavonoid Composition and Antitumor Activity of Bee Bread Collected in Northeast Portugal. Molecules [Internet]. 2017 Feb 7;22(2):248. Available from: http://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/22/2/248